This story was published in the print and online edition of The International Examiner last spring.

In early March of 2020, I was casually perusing the local news in Seattle when I froze. The strange new coronavirus, which had entered the United States, had suddenly cropped up nine blocks away from my apartment. The headline announced a patient at a nearby hospital had tested positive for Covid-19, officially making Seattle the epicenter of the first US outbreak. Days later, a global pandemic was declared and life drastically changed for everybody.

As a visual artist and a social person who thrives in community, I’d previously spent half my evenings attending art openings, live performances, and various gatherings, occasionally showing my own work at galleries. During the lockdown my neighborhood, the thriving Seattle arts district of Capitol Hill, went silent as businesses boarded up and waited. To protect my husband’s health, I took quarantine seriously and would continue to do so for more than a year. My professional career as a freelance editor provided me the good fortune to work from home. I was immeasurably grateful for that, but still lapsed into hopelessness and despair.

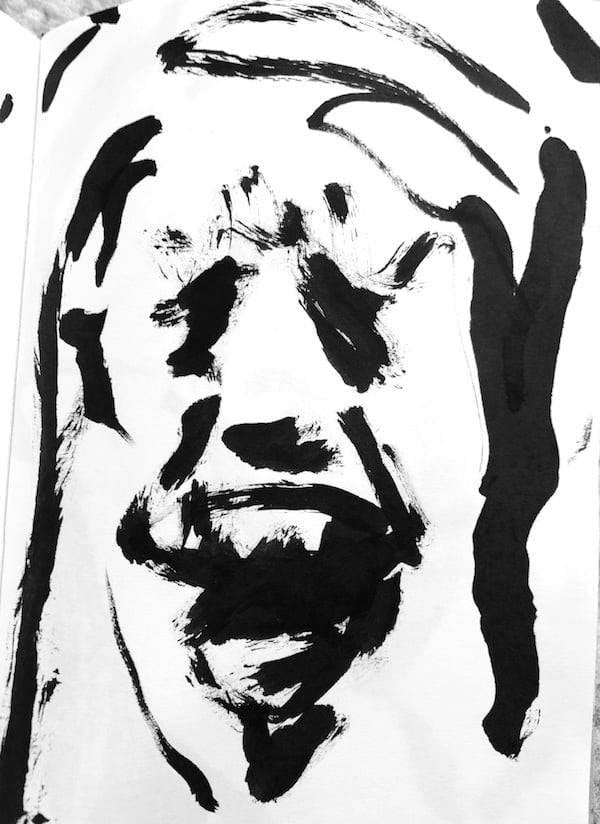

A few years ago, I had purchased an inexpensive Japanese brush pen, which is a plastic pen with a brush tip and a receptacle you squeeze to release ink. It had never worked right for me, disgorging ink at the wrong times then unceremoniously running dry, so I had given up and stored it in a drawer for three years. But during the lockdown, I began to cautiously experiment with the pen. I was surprised to find that its unpredictable ink flow made this pen the perfect tool for expressing the vicissitudes of the pandemic, from paroxysms of anguish to fragile calm. If art making is an exercise in mindfulness, working with such a frustratingly capricious instrument was even more of one. I dug out all my abandoned sketchbooks and began to gradually fill them over the pandemic.

With the brush pen, I would create drawing after drawing in 10-minute spurts. They sometimes came in an uncontrollable, primal rush; it felt like a massive purging. The black ink lay on the page, heavy as spilt blood, with a satisfying starkness. Its conclusiveness matched the existentialist gloom I staggered under. And just as the marks were impossible to erase, the global pandemic seemed unsolvable and indelible.

As cathartic as it felt, the art-making process usually didn’t make the pain go away. I noticed that it simply pooled in a different part of me or became slightly more diffused at times. Like the heavy particles in a solution, it settled under its own weight. I was forced to sit with heartbreak and then, very eventually, release it.

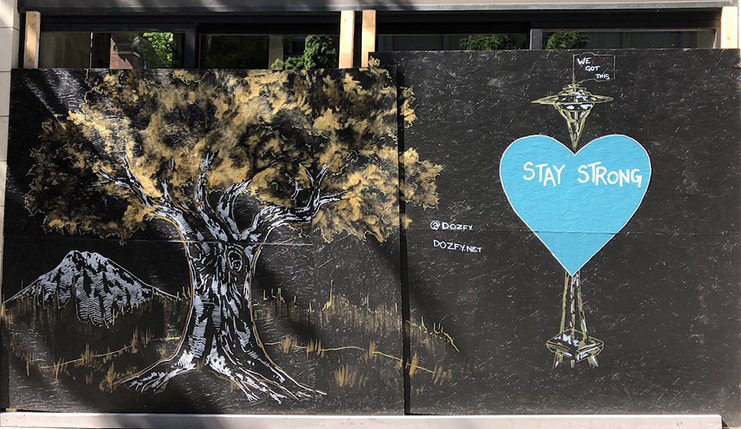

When running essential errands, I would mask up and go for occasional meditative walks around my neighborhood. I’d pass storefront after storefront, all shuttered with sweet, hopeful messages left on the plyboard nailed over the windows. See you soon. Be good. Wash your hands. Seattle, we will survive this.

One day someone sent me a video of a live heart beating, housed in a machine that restores hearts from dead patients. With each throb, it nearly jumped out of its metal box, fragile but fierce against all odds. Thump. Thump. It was such a jarring and unexpectedly moving sight that I wept. Then I drew a heart missing a sizable chunk and dedicated it to the businesses and residents of Seattle, my cherished home for the past 21 years. We were losing a vital part of ourselves minute by minute—to illness and an economic crisis—but there was still love that could sustain us for the duration, however long that was.

As the months slowly amassed into a year, I drew like I breathed. It was a means of survival and a way to arrive at some kind of truth when my insides were mudsliding into a hole. Sometimes the sketches showed a resigned helplessness coupled by overwhelming fatigue. At other times, the thickest, most impermeable despair. But the process of drawing was always clarifying because it produced a distillate of feeling on paper. It also provided a reminder that I was experiencing fleeting emotions, which did not define me, even though it often felt like they did—with a frightening permanence.

One series of drawings was titled “It’s Okay to Ugly-Cry,” as if we somehow needed permission to release the collective grief we were experiencing. It was okay, and occasionally necessary, to fall apart. To get up in the morning and cower at the foot of the bed, in dread of the new day and the worsening news. To wrap yourself in your own warm embrace, because no one else can touch you because they have Covid—or you just might. The sketch below is titled “It’s Okay to Stand as Helpless as a Toddler and Christen the Floor with Your Tears.”

Sometimes drawing was an outlet for exasperation and even humor, such as the countless Zoom meetings that many of us became all too familiar with.

I shared the sketches on social media and received a positive response. People rushed to tell me they were feeling the same thing. (“Omg this was me today!”) I wanted to build solidarity in a world that had been reduced to a two-dimensional grid on a computer screen for so many. It was impossible during quarantine to lock eyes, feel someone’s breath, and sense the air change around them as they spoke. More than one person said these sketches felt more real than reality itself, which had become at best a feeble simulacrum of pre-pandemic life.

Then there were the wistful drawings that came out of lockdown. Since my husband and I don’t own a car, we were cooped up in a smallish apartment. Our neighborhood was dense enough that neither of us felt particularly safe going outside for too long. So my landscape drawings were usually obscured by Venetian blinds or a window screen, whose fine gray mesh dulled the colors of the outside world. By contrast, the bird calls grew more intense, the air fresher, and the traffic sounds almost nonexistent. Vibrant, hand-painted murals flourished around the city.

Meanwhile, the only places I was regularly commuting to were Anxiety, Helplessness, Rage, and Depression. There were frequent mental traffic jams that trapped me between two of these undesirable locales. Out came the pen and paper.

Politics were a whole other issue. As a woman of color, I was terrified, triggered, and often suffocating in rage by the news every single day. I felt that I would either be killed by the virus or a white supremacist wielding a large gun, goaded by the presidential administration. So I used my drawings to bring awareness on social media to Black liberation, anti-Asian hate, and the critical importance of masks, vaccines, and voting.

Art making helped me stay present throughout the pandemic by documenting my maelstrom of emotions and processing them. In sharing these drawings in my personal communications and on the internet, I hoped to validate others and let them know we are truly interconnected, even during a period of unprecedented isolation. As we witnessed in the mutual aid organizations that emerged during the pandemic, compassion and empathy could encourage healing in everyone. And art is a perfect vehicle for delivering those gifts.

Ultimately, these raw sketches forced me to embrace the fullness of this collective experience—our shared trauma—and draw strength from it while building community. Art has a way of reminding us that we are alive and have more in common with each other than we think. The best thing is we can always rely on it to remind us of our own humanity, even in the most humbling and dire of times.